Tilly’s business is easy to understand: they are a mostly brick-and-mortar, teen/young-adult apparel retailer with 241 locations (137 in malls). I won’t spend too much time describing the business; I would recommend checking out their website/Instagram to get a sense of the brand. While Tilly’s is a mostly unextraordinary business, there is a price for everything, and I am going to attempt to demonstrate that Tilly’s is cheap both on an absolute basis and relative to the sea of brick-and-mortar retailers that screen cheaply at the moment.

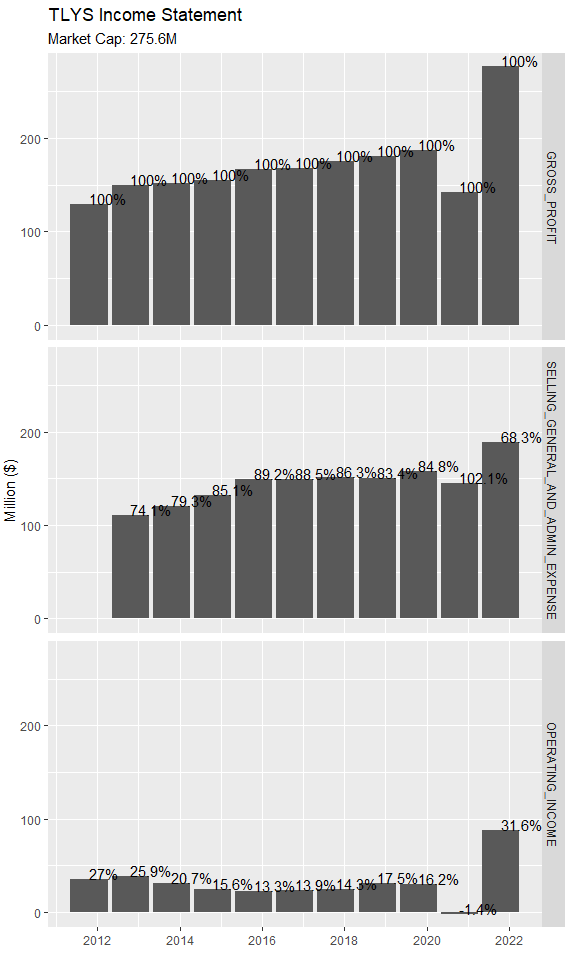

Let’s go right into the financials, starting with income statement.

A few features jump out. First, we can see that the most recent year has been the strongest ever by some margin, with a jump in revenue driving operating leverage and record profitability. Second, we note that the year proceeding last was poor, with COVID-related lockdowns impacting store traffic and driving a small net loss. Prior to that we observe a stable business, with top-line growth yielding a stable bottom-line.

When projecting performance over the next few years, I think it is best to benchmark to performance in the years prior to the pandemic. We should not count on profitability approaching what it has been over the last year, as the 2021 sales environment — which benefitted from the perfect cocktail of stimulus checks and reopening — is unlikely to be repeated. Management has said as much in this telling excerpt from the most recent earnings call (which drove a meaningful correction in shares):

Before getting into my expectations for earnings moving forward, I want to give more details on the income statement and then connect it to cash flows. First, why have we seen generally rising revenue and gross profit but flat-ish operating income? Here is the same data, but with SG&A added and with %-of-gross-profit labeled on each bar:

So we can see operating income as a percent of gross profit has fallen from ~26.5% back in 2012 to ~17% pre-pandemic. The contour can be explained by examining gross profit per square foot:

From 2012-2016 the company aggressively grew square footage and sales-per-sq-ft compressed. Comparable sales for the period are fairly stable, which indicates the margin compression mostly has to do with stores needing time to mature in new markets rather than declining earnings in established stores. Then from 2016 onwards new management (new CEO Ed Thomas) dramatically slowed expansion which allowed profit-per-sq-foot to slowly upward inflect, though the metric remains below 2012/2013 numbers despite comparable sales numbers in 2019 surpassing the previous 2013 peak. Going forward, my guess is that gross-profit-per-sq-ft treads water in the 10 to 11 cent range, allowing for minor operating income growth as top-line numbers continue higher. Management seems to expect the same for the next quarter, guiding to 145.5M of revenue in Q1 at the mid-point. While this was a disappointment relative to 2021 results, it seems much more satisfactory when compared to pre-pandemic results:

Let’s turn to the cash flow statement - are those operating profits translating into cash?

We can see that, excluding the pandemic-influenced last 24mo, annual FCF (net of stock-based comp) has averaged $22.1M on a 3-year basis and $21M on a 5-year basis with reasonable stability. This compares to adj. net income on the same 3-year basis of $20.3M and on the same 5-year basis of $16.9M. FCF has been able to outpace net income as D&A runs significantly higher than capex following the slowdown in pace of store expansion.

Now lets turn to valuation. First note that TLYS carries cash of $139.2M and no debt aside from operating lease liabilities. Given a market cap of $268.8M, that puts EV at $129.6M. Dividing the 3-year, pre-pandemic FCF number by the EV gives a FCF/EV yield of 17.1%. In my view this yield is too high for a business that, while cyclical, now has a lengthy track record of stable results. As noted above, my base case is for operating profits to incrementally float higher with the top-line (from 2019 base) over the next few years, and while it is always possible that TLYS will lose favor with consumers, such a high FCF/EV yield provides substantial margin-of-safety should the company become a melting ice cube.

Before turning to a relative value analysis, I want to address the elephant in the room. Why is this company holding half its market cap in cash and doesn’t that call into question the incentives/judgement of management as far as capital allocation? I have reviewed the last few years of earnings calls, and I was unable to come up with a good reason for management’s cash hoarding. Whenever they are asked about it they repeat something along the lines of: “the board reviews our cash position regularly and that’s all we have to say”. This is frustrating as a shareholder and is unlikely to change in the near-term given the company is controlled by class B super-voting shares. On the positive side, management doesn’t seem interested in building the cash position further: they have regularly paid out significant special dividends and recently issued an authorization to repurchase shares following the drawdown post-earnings. I think it is fair to discount the value of cash given the management situation - if we use a 67% multiplier on cash the FCF/EV yield falls to 12.6%.

How does TLYS compare to some of the other “cheap” retailers? One way of comparing is to examine pre-pandemic FCFs and compare with current EVs. We can then consider the FCF yield in the context of pre-pandemic earnings trajectory. As a first step in this analysis, here is a list of competitors sorted by unlevered yield (which I define as mean unlevered FCF for the 5 years proceeding the pandemic divided by current EV).

With the exception of Foot Locker, whose ability to replicate pre-pandemic results is highly in question following Nike’s pullout, Tilly’s tops the list on an unlevered basis. It is only rivaled by firms such as the department stores, which have been melting ice cubes for a long while now. But what if we discount the value of TLYS cash for the reasons mentioned above? If we use a 12% unlevered yield for TLYS, it falls to the middle of the pack. The six companies above TLYS, however, all have declining pre-pandemic earnings trends (URBN had the best of this group, though it was still in decline). TLYS seems attractive in this context: significantly higher in yield than alternatives with similar pre-pandemic growth trajectories. The recently initiated buyback program makes the opportunity even more attractive, as management is implicitly deploying the high FCF yield back into a highly yielding security.